The discovery of gold in the 1850s started a series of rushes that transformed the Australian colonies.

The first discoveries of payable gold were at Ophir in New South Wales and then at Ballarat and Bendigo Creek in Victoria.

In 1851 gold-seekers from around the world began pouring into the colonies, changing the course of Australian history.

The gold rushes greatly expanded Australia’s population, boosted its economy, and led to the emergence of a new national identity.

Geelong Advertiser, 14 October 1851:

There are, we should say, about a thousand cradles at work, within a mile of the Golden Point, at Ballarat. There are about fifty near the Black Hill, about a mile and a half distant, and at the Brown Hill Diggings there are about three or four hundred more; to say nothing of hundreds on the ground not yet set at work. Allowing five for each cradle, the population within a radius of five miles must be a population of about seven thousand men.

The gold rush in live-sketch animation, as told by historian David Hunt

Discovery of gold in Australia

There had been multiple gold finds in New South Wales (Bathurst and Monaro), Tasmania and what would become Victoria prior to the ‘official’ discovery of the precious metal by Edward Hargraves near Orange in 1851.

In 1841 Reverend William Branwhite Clarke, one of the earliest geologists in the colony, came across particles of gold near Hartley in the Blue Mountains.

In 1844 he mentioned it to Governor Gipps who reportedly said: ‘Put it away Mr Clarke or we shall all have our throats cut’.

Gipps feared that mutiny would result if the people of New South Wales, the majority of whom were convicts or ex-convicts, found that gold was within easy reach.

In 1848 mineralogist William Tipple Smith found gold near Bathurst and the following year revealed the find to the NSW Colonial Secretary Edward Thomson. Research by one of Smith's relatives, Lynette Silver, established that Smith’s find was the first discovery of payable gold. However, he was denied the recognition and monetary reward, which was ultimately claimed by Edward Hargraves.

The government’s attitude to gold discoveries changed in 1848 with news of the California gold rush. The promise of fortunes to be had across the Pacific led thousands of men to leave the colony, creating labour shortages and economic depression.

Governor Charles FitzRoy had heard rumours of the gold to be found in New South Wales and believed a mineral discovery in the colony could reverse the economic downturn.

He convinced the British Government in 1849 to appoint a government geologist, Samuel Stutchbury, and offered a reward to anyone who found a commercially viable amount of gold.

Edward Hargraves

Edward Hargraves was a jack of all trades: farmer, storekeeper, publican, pearl-sheller and sailor. In 1849 he sailed for the Californian gold rush.

He failed to find his fortune but was struck by the topographical and geological similarities between California and the interior of New South Wales.

In January 1851 he returned to the colony and immediately headed inland, convinced he would find gold and, more importantly, claim the government reward.

New South Wales gold rush

Near Bathurst, Hargraves enlisted the support of John Lister and brothers William and James Tom. Within weeks they had discovered a small amount of gold at a site Hargraves named Ophir, after a port city of great wealth mentioned in the Old Testament.

Hargraves returned to Sydney in March 1851 and presented his samples to the government. Samuel Stutchbury was sent to confirm the strike, which he did.

Hargraves was eventually awarded the £10,000 prize, which he refused to share with Lister or the Tom brothers.

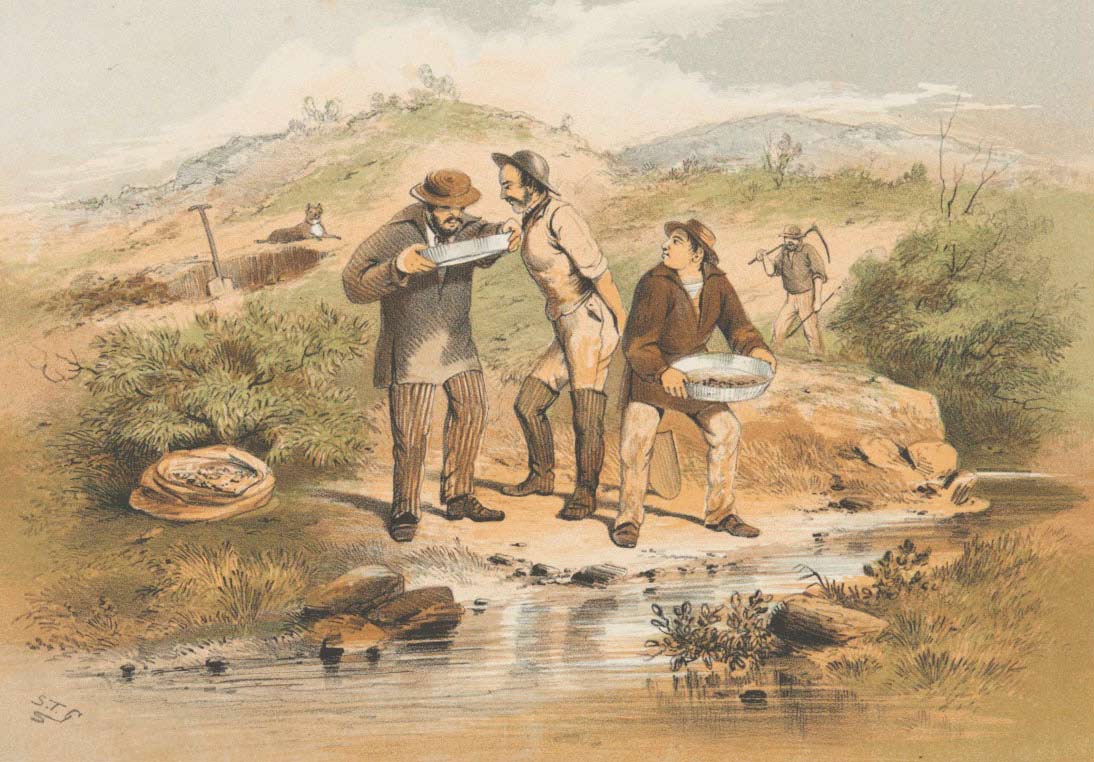

News of the find was promptly published in the Sydney Morning Herald and by 15 May 1851, 300 diggers had arrived in Ophir. The rush was on.

Victorian gold rush

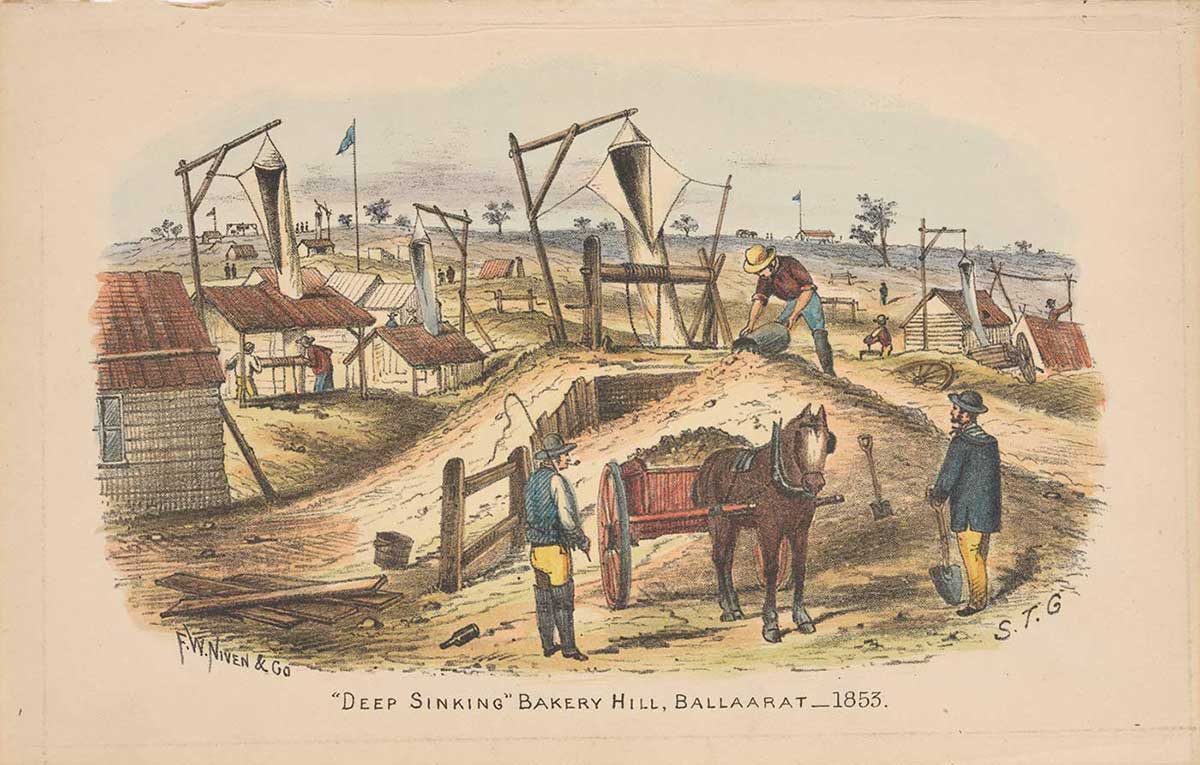

In the newly established colony of Victoria, men began to flood north to the New South Wales goldfields. The Victorian Government responded with the offer of a reward of £200 to anyone finding gold within 200 miles of Melbourne. Within six months, gold was discovered in Clunes, and then Ballarat, Castlemaine and Bendigo.

The Victorian rush would dwarf the finds in New South Wales, accounting for more than a third of the world’s gold production in the 1850s.

Migration boom

The discovery of gold started a series of rushes that transformed the other Australian colonies. Significant deposits were discovered in Tasmania from 1852, in Queensland from 1857 and in the Northern Territory from 1871.

In the 1890s a new series of rushes were triggered by the discovery of huge gold fields at Kalgoorlie and Coolgardie in Western Australia.

Between 1851 and 1871 the Australian population quadrupled from 430,000 people to 1.7 million as migrants from across the world arrived in search of gold.

The largest non-European group of miners were Chinese, most of whom were bonded labourers who suffered discrimination from the government and fellow diggers. It’s estimated that by 1855 there were 20,000 Chinese on the Victorian diggings.

Among the larger group of migrants were many men and women bringing new political ideas to the young colonies.

Initially, the colonial establishment resisted such progressive thinking as a threat to their authority and the resulting tensions culminated in the Eureka Stockade. But a groundswell of public opinion brought about a series of world-leading social experiments, such as the secret ballot, the eight-hour day and the formation of the Labor Party.

Australia’s huge reserves of gold made the country a destination for people from around the globe and by the end of the 19th century the rushes had helped create a wealthy, liberal society with a standard of living that was the envy of the world.

Curator Stephen Munro on the significance of the Bealiba gold nugget found near Bendigo.

In our collection

Explore Defining Moments

References

William Tipple Smith recognised by the New South Wales Government

Robyn Annear, Nothing but Gold: The Diggers of 1852, Text Publishing, Melbourne, 1999.

Weston Bate, Victorian Gold Rushes, McPhee Gribble/Penguin, Fitzroy, Victoria, 1988.

David Goodman, Gold Seeking: Victoria and California in the 1850s, Stanford University Press, Stanford, California, USA, 1994.

Geoffrey Serle, Golden Age: A History of the Colony of Victoria, 1851–1861, Melbourne University Press, Carlton, Victoria, 1977.

Lynette Silver, A fool's gold?: William Tipple Smith's challenge to the Hargraves myth, Jacaranda, Milton, Queensland, 1986.